Welcome back to DUM DUM Zine’s Text Message Interviews! You’ll get ’em once a month in concordance with our “VOX & Voices” reading series. This month we interview Jen Hofer: L.A.-based poet, translator, social justice interpreter, teacher, knitter, book-maker, public letter-writer, urban cyclist, and co-founder of the language justice and language experimentation collaborative Antena and the language justice advocacy collective Antena Los Ángeles.

Hofer will be reading at the DUM event TONIGHT joined by Joey Revenge, Diana Arterian and our musical act, Emily Gold! Read up now to #GetDUM in advance of our reading on the charming patio of Stories Books & Cafe!

Taleen Kali (DD): Morning Jen! Taleen here, ready to start our txt msg interview if you are!

I love your zine library in your home. Could you give us a quick backstory on what inspired you to catalog all your zines?

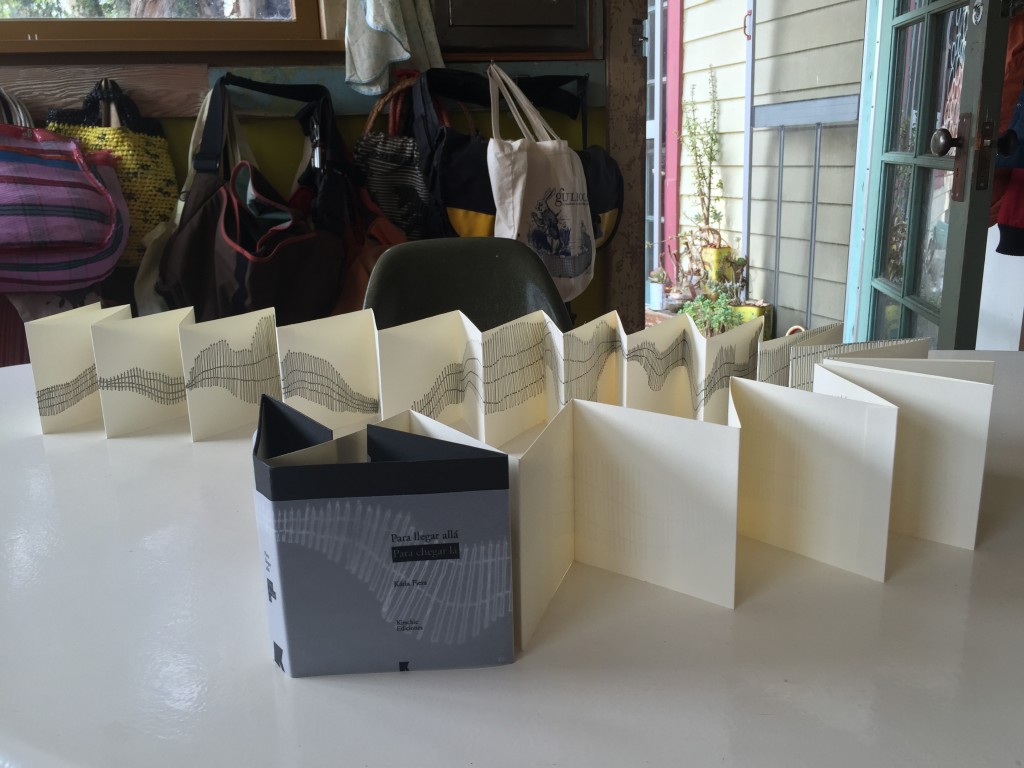

Jen Hofer (JH): I’m glad you love the library!! It makes me so happy when people use it for inspiration, to learn about DIY bookmaking techniques, or just as a reading resource. Anyone is welcome to visit it and use it so please be in touch (jen@antenalosangeles.org) if that’s something you’d like to do! It’s more of a chapbook library than a zine library (depending on how you define “chapbook” and “zine,” I suppose…) — though there are some of each, and there’s lots of overlap between those two categories, of course.

For 5+ years I’ve been teaching a class at CalArts called Tiny Press Practices, in which we consider DIY bookmaking and tiny-press publishing as tools for building the autonomous literary communities and conversations we want to participate in — rather than waiting for permission to “go public” with our work. We read tons of chapbooks and zines from all kinds of tiny and micro press projects, and between my decades of interest in those publications (and hence collecting them without even meaning to!) and the more organized collecting that happens when I teach tiny press practices, I’ve developed quite a gathering of DIY publications.

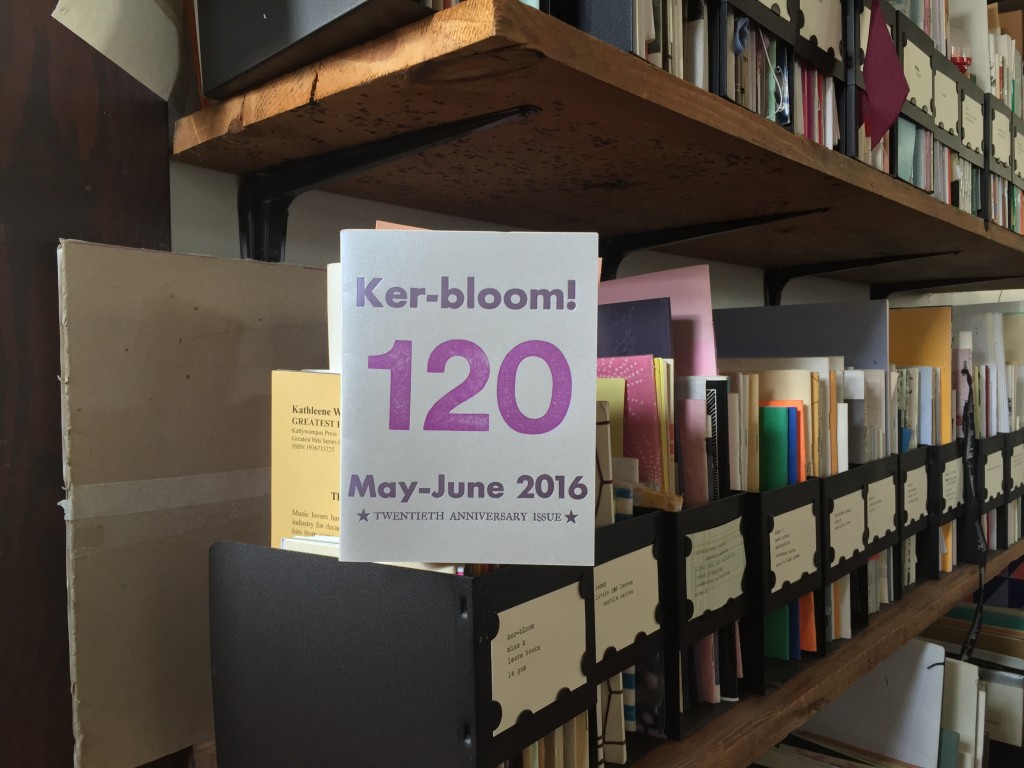

I used to have them on display over the fireplace in my living room, but there were piles and piles of them and I noticed that people were shy about pulling out ones they wanted to read, because it seemed like the entire mountain might topple if you disturbed its precarious balance. I’d been wanting to reorganize for ages, and finally just put some time and energy and money into it — money because I bought metal display boxes for all the publications from Brodart, an online library supply shop, and I hired a good friend to help me catalogue (and to keep me honest so I myself would work on it too!). Right now there are 1675 publications catalogued in the collection, but I have a box of items I need to catalogue and shelve sitting in my living room…

DD: Possible to send us photos of 3 zines you have been thinking about or reading lately from your personal collection?

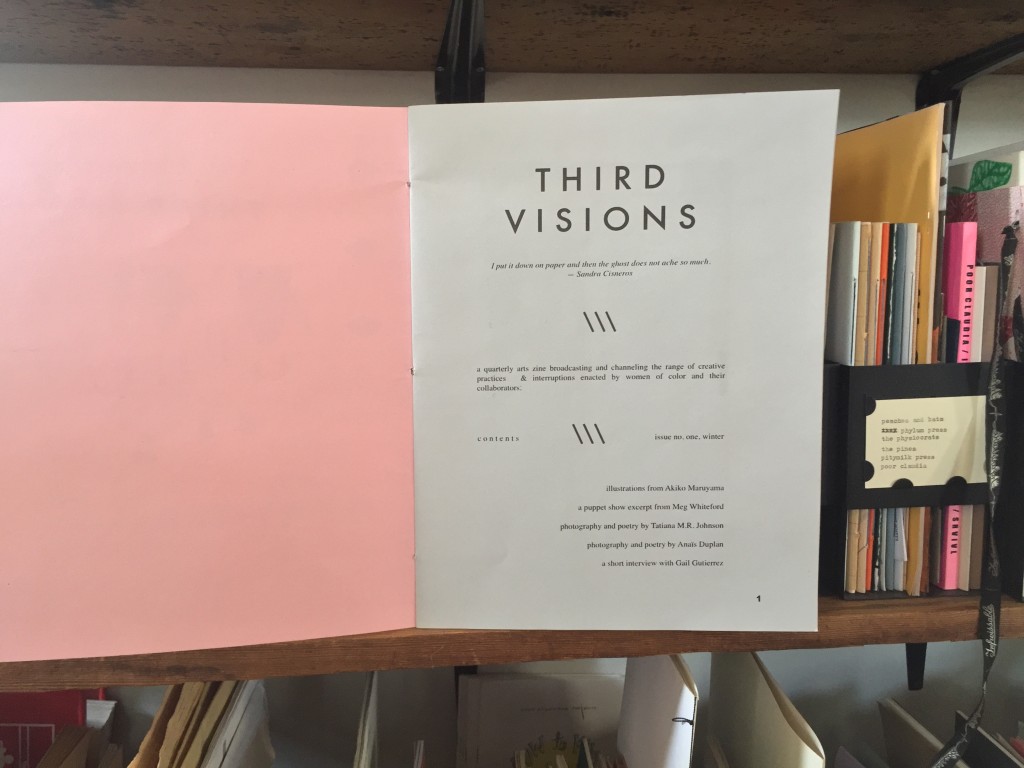

Third Visions, a project of Loose Pleasures, ed. Allison Conner

DD: Amazing! My next question, which is part of DUM DUM Zine’s “1 Question Interview” series: what keeps you inspired and astonished as a creator?

JH: There are many things that keep me astonished and inspired. I often ask myself — which are the conversations I most want to participate in, and how can I make work that either helps to create those conversations, or makes it possible for me to engage in them?

I am endlessly inspired by the work of other makers, thinkers, and activists I already know and by many I encounter who I do not yet know (or might only know through their works). I also ask myself, all the time, how can I extend the platforms and resources I am offered to other folks who might not otherwise have access to them? The projects that become possible when I view opportunities I am offered in this way–as invitations to disperse and proliferate–are hugely inspiring to me. And I am astonished, both negatively (i.e. sparked to action by rage and incredulity and solidarity) and positively (i.e. sparked to action by delight and wonder) by the way the world works, how it is and how it might be.

DD: There is such a visible thread of communication, of possibility, of expansion, as a through-line in all your print projects and and I perceived this even before I came across your work formally.

I love the spark of rage you bring up, and how that rage manages to translate into something so inviting and communicative in your work. Too often is silence and invisibility a knee-jerk reaction, so being able to use the rage for expansion and art making is such a transformative practice. I think all artists could use more of this (myself included)! Can you think of the most recent example in your practice?

JH: I can think of three examples of rage sparking art-making from the past week–I think there’s a lot to be outraged and enraged about in this world, and I think that art should respond to rage–if not to soothe it (which might be nice sometimes!) then to spark more rage, to encourage creative resistances and solidarity through inventiveness.

1. I’m writing a series of poems–hoping it will be a book-length series–called conditions. Each poem is also titled “conditions.” The poems respond to the brutalities of the present moment–that is, the “conditions” and landscapes different kinds of bodies and selves move through right now. I spent some time last week thinking about Ashaki Jackson’s Writ Large Press chapbook Surveillance, and about the crackdown on Black Lives Matter activists like Jasmine Abdullah Richards (being sentenced today June 8 for a conviction of “lynching” which would be laughable if it weren’t so deadly serious), and about the ways cops get off without charges after murdering people society doesn’t value. And a few “conditions” were sparked by that thinking.

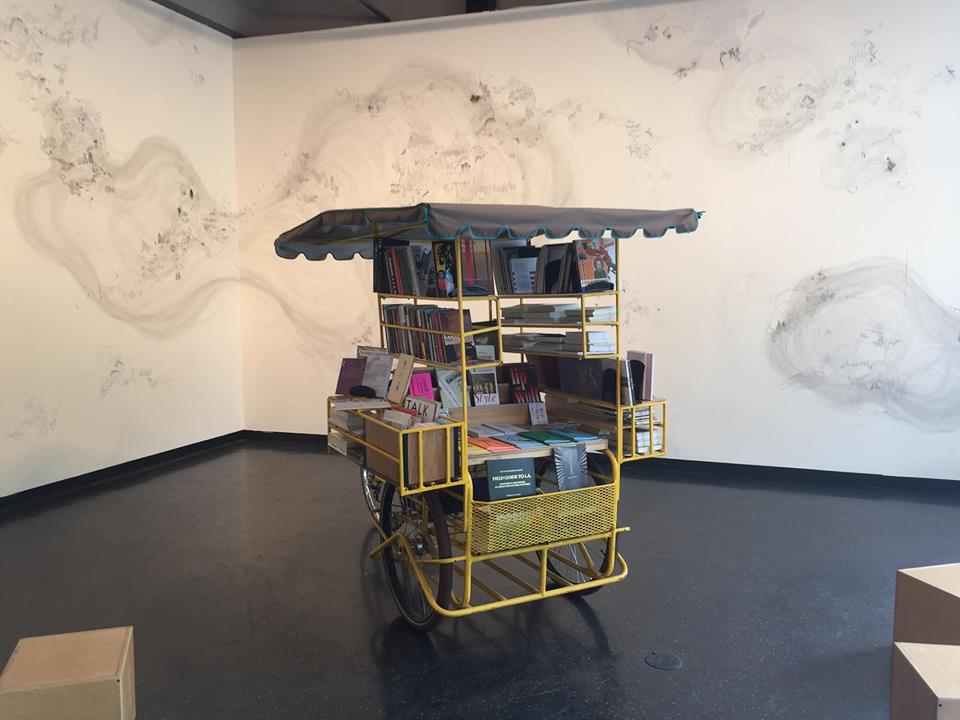

2. Last weekend the AntenaMóvil residency at Grand Central Art Center in Santa Ana opened and I was talking to a Chicanx writer at the opening about how many times she was told not to mix Spanish and English in her poems–that it’s better to write in only one language, and better still if that language is English. The AntenaMóvil currently features books from small independent presses from the US and Latin America, with a focus on bilingual and multilingual writing, translations into English from all over the world, experimental writing in Spanish from Latin America, and innovative texts by U.S. writers of color. That project exists in direct and enthusiastic resistance to monolingualism, monoculturalism, and the still too prevalent idea that a person “should” or “should not” write a particular way based on their background, their identity, their langauge preferences. the color of their skin, or anything else.

3. Insofar as language justice organizing is also part of my art-poetic practice–which it is–then the many examples of unnecessary English-language dominance in spaces that could easily be effectively bilingual or multilingual incite the rage that leads to my passion for advocating for listening and conversing across language difference–and hence across many other forms of difference. It happens all the time–last night, for instance, at a community meeting where Antena Los Ángeles was interpreting–that I welcome a participant to the space and explain that both English and Spanish will be spoken so if the person is not comfortable in both languages they should get interpreting equipment, and the response, often accompanied by a scoff, is “oh I speak English, I don’t need interpreting equipment”–as if nothing of value or significance could possibly be spoken in a language other than English. If I’m not going to be consumed by the rage and sadness that kind of racism drills into me, then I have to make something out of it.

DD: conditions sounds so powerful especially considering the political climate right now. I know you experiment with different formats: do you know the format the work will take yet?

JH: The poems in conditions are all 235 words long, in solid prose blocks. They all look exactly the same — tightly controlled boxes. I’m not sure why that’s the form, exactly (and perhaps I don’t need to be sure about that). I wrote the first one as part of a collaboration I did with TC Tolbert, for our chapbook titled Conditions/Conditioning, published in 2014 by NewLights Press. The form and thematics and momentum of the work really moved me so I kept writing them, maintaining exactly the form (word count and prose format) of the first one in the series.

DD: I’ve been following the AntenaMóvil journey since you told me about it last year. How did you find the cargo tricycle? What was the experience like of deciding how to display the works themselves? Also, I’m wondering whether you curated the bilingual and multilingual books from your personal library–was there any other process in finding or seeking out other works?

JH: My collaborator and co-founder of Antena, John Pluecker, originally found the cargo trike — it used to sell snacks on the East End of Houston, where JP lives. We worked with another collaborator, Jorge Galván Flores, and some other folks, to retrofit the trike to become a bookmobile and mobile workshop/event space, and to electrify it so it could actually function in the terrain of Los Angeles. The AntenaMóvil has been used — and will be used — in a variety of ways: as a space to display books and other artworks, as a mobile printing press, as a site for workshops and conversations and writing, and hopefully in many ways Antena hasn’t yet imagined. (Feel free to be in touch if you have ideas for how to use it!! jen@antenalosangeles.org.)

There hasn’t been much of an organized process of deciding how to display the books. We make selections for which books to bring with us or which books or presses to feature based on specific events the AntenaMóvil will visit. When it’s installed at a museum or art center, as it is now, the books are usually organized by press project, with certain featured books displayed together. Right now the feature displays include local Southern California small and tiny presses (Econo Textual Objects, Eohippus Labs, Inlandia Imprint, Kaya Books, Loose Pleasures/Third Visions, Phoneme Media, Seite Books, and Writ Large Press), innovative writing by African-American poets (Ashaki Jackson, Douglas Kearney, Dawn Lundy Martin, Fred Moten, Morgan Parker, and Claudia Rankine), and poetry in indigenous languages translated into Spanish or English or both.

Actually, none of the books are from my personal library. The majority of the books from small independent presses in the U.S. come through the amazing non-profit distributor (run by poets of course!) called Small Press Distribution. Without their support, the AntenaMóvil couldn’t exist, literally. The books from local SoCal presses come from personal relationships–agreements I make with specific editors, or in the case of Seite Books, with booksellers. SPD and all the amazing editors with whom I’m working directly for the AntenaMóvil project are hugely generous–they let Antena have books on consignment, and we pay for what we sell. That enables us to have a much larger selection than we might otherwise.

The books from Latin American independent presses are slightly haphazard, as I rely on libro-traficantes to help me get books to the U.S. without spending a fortune on shipping. I do research as best I can, reading online and asking poet friends in Latin America for suggestions of presses that might be interesting for the AntenaMóvil, and I then contact the editors to try to buy books from them at a discount and figure out how to get the books to the U.S. without breaking the budget. The AntenaMóvil, which features small-press tiny-press, and DIY publications with bilingual and multilingual writing, texts in translation into English from all over the world, experimental writing in Spanish, and innovative texts by U.S. writers of color is, in a way, my dream library–so I guess in that sense it’s representative of my personal library!

DD: More dream libraries come true everywhere! And for my final question: do you believe literary translators have a certain responsibility to social activism? And In turn, do you think social activism depends heavily on literature/the arts?

JH: I believe that everyone has a certain responsibility to social activism, though that activism — and what different people experience as “the social” — will look and feel and sound different for every person. I think there is a particular responsibility to awareness — and perhaps also to activism — when artists are working across languages or cultures, as translators do. How can you not think about politics when you are bringing work from one language into another? How can you not think about which languages are dominant in the world, how that dominance manifests, the relationship of language to race and class, the ways that translation and other cross-language practices can invite radical listening across difference?

And how we encounter difference, the ways we locate commonality and the ways we coexist in a neighborly way alongside people with whom we may not locate commonalities — that is, the ways that difference can be welcomed and seen as a form of nourishment and learning not only through making-same but also through remaining-different — those realms and actions and relations are inherently political, and should, I think, be approached from an activist perspective. What’s an activist perspective, in my view? A perspective that acknowledges how imbalanced and fucked up the world is, and takes active, thoughtful steps toward re-balancing and un-fucking-up.

For me personally, activist practice and aesthetic practice are entirely intertwined. I know that’s not the case for everyone and that’s all right with me. I’m the kind of person who can be radicalized and incited to action, over and over, by a poem or a film or a song or a collage–and by other non-artistic provocations as well, of course. I know that artistic works aren’t catalyzing to everyone, and I’m comfortable with that — what’s important, I think, is to be open to being catalyzed, no matter what. I love to hear about the sparks that inspire others, just as I love to share the sparks that inspire me.

*

Friday, June 10, 2016